NZ travel: A visit to Rangihoua Heritage Park in Northland

Northland’s Rangihoua Heritage Park not only commemorates New Zealand’s first European settlement but also holds powerful and varied meaning for its many visiting hikers

Bay of Islands, Northland, New Zealand (image by Jacqui Gibson).

It's a warm Sunday morning in the northern Bay of Islands when Hugh Rihari greets me with a smile outside the farmhouse he shares with wife Raewyn.

Armed with a handful of papers, including two archaeology reports published by the University of Otago, Hugh ushers me to an empty chair on the porch.

We’re not seated in view of the pohutukawa-lined foreshore of Te Puna inlet just metres away. But behind us I can hear the occasional woosh of the incoming tide mingling with the warble of tūi.

Hugh is 76 years old, slight in stature and sports a brushy grey moustache. One of the region’s most influential kaumātua (elders), Hugh is also kaitiaki (guardian) of an historic pā once home to Te Pahi and Ruatara – Ngāpuhi rangatira (chiefs) who traded and travelled widely in the early 19th century and were largely responsible for New Zealand’s first permanent European settlement.

Raewyn and Hugh Rihari of Te Puna, Northland, New Zealand (image by Jacqui Gibson).

It’s a local history Hugh is often asked to recall. Just a few days ago, he met two busloads of Kerikeri students and teachers and gave a history lesson on his whanaunga (relatives). Hugh traces his links to Ruatara’s wife, Rahu, and to Te Pahi through a tūpuna’s (ancestor’s) relationship with Te Pahi’s mother.

Meeting the group at Rangihoua Heritage Park nearby, Hugh pointed to the terraced pā in the distance, explaining how its strategic position helped Te Pahi, Ruatara and their tūpuna flourish in the Bay of Islands over centuries.

“‘Without Rangihoua pā,’ I told them, “‘New Zealand’s first European settler community would’ve washed up on some other shore’,” says Hugh. “The 1800s were exciting, but dangerous times. That pā gave Marsden’s missionaries much-needed protection. And because they settled in the Hohi valley where it was hard to grow crops, the community gardens that surrounded the pā, gave the missionaries food to stay alive.”

Rangihoua Heritage Park is a 44-hectare park on the Purerua Peninsula about 40 minutes’ drive from Kerikeri or three-and-a-half hours’ drive from Auckland.

Formally recognised by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga as a heritage area in 2007, the park officially opened in 2014 to commemorate 200 hundred years since the founding of Hohi Mission Station, New Zealand’s first European settlement.

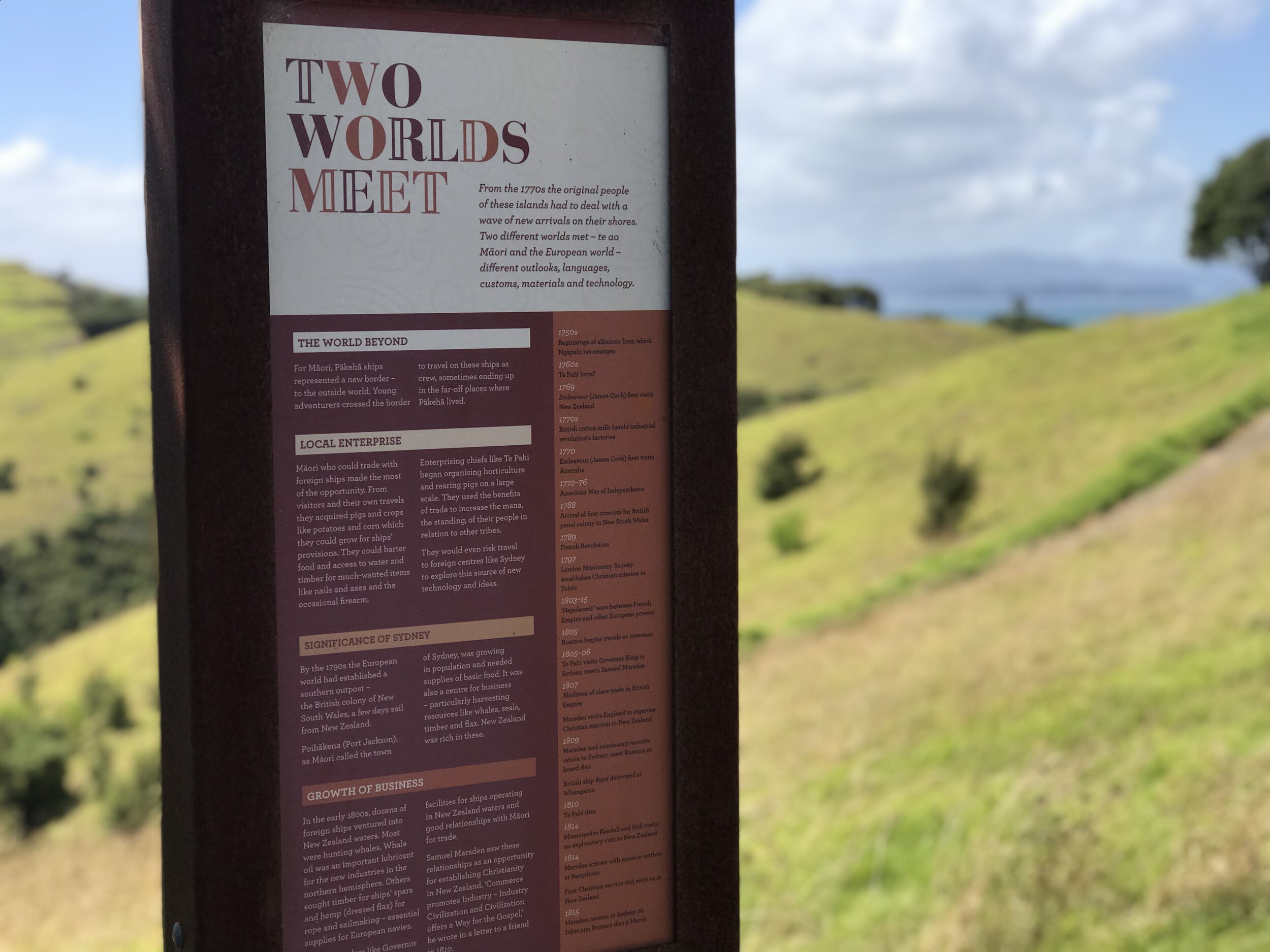

Planned and directed from Australia by the Reverend Samuel Marsden, the mission operated under the protection of local Māori from 1814 until it was abandoned in 1832. Today, it doubles as a thoughtfully designed and well-signposted heritage track that starts at a shelter called Rore Kāhu at the top of the hill and finishes on the foreshore of Rangihoua Bay.

The entrance to Rangihoua Heritage Park is marked by an architecturally-designed shelter called Rore Kahu (image by Jacqui Gibson).

On my visit to the park, I encounter a church group of a hundred or so sodden people winding their way back up the valley through soft-falling rain. As they pass by, they cheerfully call out, “kia ora!”

A couple stops to chat. Despite the grey day, the pair tell me they’ve picnicked on the grassy terraces of Rangihoua Bay where three missionary families (the Kings, the Kendalls and the Halls) came ashore in a bid to convert Māori to Christianity.

The couple has viewed the colourful exhibition signs explaining where New Zealand’s first school house was erected and paid their respects to the missionaries buried at the King family plot.

From information plaques lining the track, they’ve learned how Rangihoua’s first pioneers spent their time: building, teaching, blacksmithing and twine spinning for some of the men; sewing, cooking and raising children for most of the women.

Meanwhile, kids in wet togs trudging up the track have swum in the same ocean where a brig named Active safely offloaded missionaries, crew and cargo more than two centuries ago.

By the time I cross the river onto the beach, final stragglers are taking selfies with the Marsden Cross, a monument marking the country’s first Christian service, before heading back up the hill.

“The power of the site,” Hugh tells me, “is that it means different things to different people. For some, it’s about reconnecting to that early Christian heritage and imagining the strength and resolve it took for the families to settle halfway across the world in a difficult and dangerous place.

“For people like me, Rangihoua is the place of my ancestors. It’s where two vastly different cultures tested the idea they could live side by side. It is where this country’s bicultural story first began.”

In 2003, Hugh was invited to join seven others with family or spiritual ties to Rangihoua to form the Marsden Cross Trust Board.

“The goal of the Trust was to acquire Rangihoua and use it to tell the story of our tūpuna and the missionary settlement. I was 100 percent on board with that. From the outset, I hoped the park would become a place where people could learn how the two cultures of New Zealand came together.”

In 2012, a two-year archaeological dig, jointly carried out by the Department of Conservation (DOC) and the University of Otago, revealed several clues about early life at the mission: evidence of missionary buildings, including the school houses, as well as remnants of personal items such as tools, tin-glazed earthenware and tobacco pipes.

Data collected from the dig, as well as historical information provided by Hugh, fellow trust board member John King, DOC and Heritage New Zealand, formed the basis of two major reports on the archaeology of the mission station. Both reports were later used to design the park layout and signage.

Hugh estimates around 5,000 people visit Rangihoua every year. He is happy to share stories of local rangatira and their interactions with Marsden’s missionaries.

“I just think it’s so important future generations understand the full history of our country and have a balanced view about those early days. At Rangihoua, they can do that. It’s a beautifully laid out park. And the stories of both Māori and Pākehā are right there, side by side, for everyone to enjoy.”

Marsden Cross, Rangihoua Heritage Park, Northland (image by Jacqui Gibson).

GETTING TO RANGIHOUA HERITAGE PARK

Rangihoua Heritage Park, in the Bay of Islands is 40 minutes’ drive from Kerikeri and 90 minutes from Whangārei.

Once you reach the Hohi Road carpark, walk to Rore Kāhu, the park’s central meeting place where panoramic views of the valley will open up before you.

Take the pilgrimage path that winds down the valley with plaques telling the story of early Māori settlement, the beginnings of Christianity in New Zealand and the layered story of Māori and European contact.

TOUR THE HERITAGE SITES OF NORTHLAND

Rangihoua Heritage Park is one of nine Northland heritage sites within the Landmarks Whenua Tohunga programme, a joint initiative of the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, the Department of Conservation and Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

Landmarks Whenua Tohunga helps visitors learn more about New Zealand history.

Other Landmarks sites include Cape Brett Rakaumangamanga, Clendon House, Kororipo Heritage Park, Māngungu Mission, Pompallier Mission, Ruapekapeka Pā, Te Waimate Mission and the Waitangi Treaty Grounds.

Tour Northland’s significant heritage sites by downloading Heritage New Zealand’s ‘Heritage Trails’ driving app.

Select ‘On a Mission’ from the ‘Path to Nationhood’ tours to begin at Rangihoua Heritage Park.

To take a smartphone audio tour when you’re there, visit: rhp.nz/tour

This story was first published in Heritage New Zealand magazine.